Quality of Government and Subjective Poverty in Europe

Baldini M., Peragine V., Silvestri L., 2018 – CESifo Economic Studies

Nowadays, it is universally acknowledged that the quality of institutions is of enormous importance for people’s living standards. Their link concerns not only material well-being, through a positive effect of the quality of institutions on the possibilities of economic growth of countries, but also on subjective well-being of people. In high-quality government countries, for example, life satisfaction is on average higher than in countries with fragile institutions, as is support for a democratic political system.

Many studies have found a positive link between the quality of institutions, good governance and subjective wellbeing. The link may be not only indirect, if good governance facilitates economic growth or other dimensions that are important for people’s well-being, but also direct, if life is made easier and safer by government action. For example, the ability to reach the places of study or work may be severely hampered by lack of safety in the streets or by an inefficient public transport system. Similarly, the presence of public health-care services is not a sufficient condition to guarantee adequate health care, if the quality of these services is bad.

What are the implications of institutions and their quality for subjective poverty? The poor quality of public services may force a household to buy, in the private market, goods or services that are substitutes for the public ones, in important sectors such as health care, transport, or education. Therefore, this household actually has a lower standard of living, despite showing similar income levels. Further, the presence of corruption or too much bureaucracy may produce a sense of insecurity that hampers the perspectives of improvement in personal economic conditions. Since one of the main objectives of national and local governments is the increase in their citizens’ living standards, the observation of levels of subjective poverty and well-being can provide important information about the effectiveness of governments’ attempts to ensure such a goal. Usually, however, the impact of the quality of government (QoG) on personal well-being is not adequately recognized by empirical research.

In a recent study, Quality of Government and Subjective Poverty in Europe, published in CESifo Economic Studies, Massimo Baldini, Vito Peragine, and Luca Silvestri concentrate on this relationship making use of data on the quality of government at the subnational level in Europe gathered by the ‘Quality of Government Institute’ of the University of Gothenburg through a survey carried out in 2010 and then repeated in 2013.

The survey was conducted over the EU member countries and involved around 34,000 individuals in 2010 and 85,000 in 2013 who were asked about their opinions on three concepts that are considered key dimensions of the general concept of the QoG: the quality of the services, whether they are delivered with impartiality, and the possible presence of corruption. Data from this survey allow to create the ‘EQI’ index – European Quality of Government Index – both at national and subnational level.

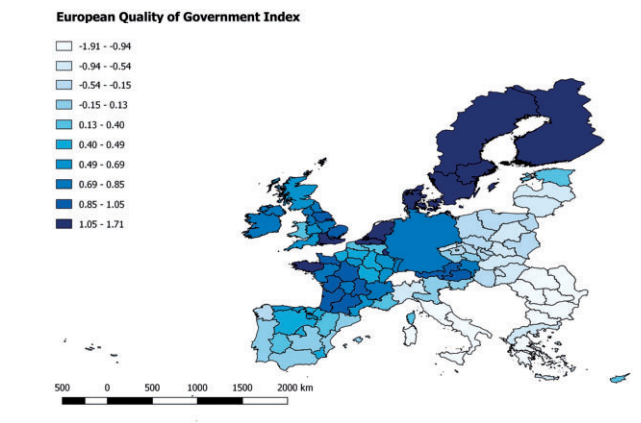

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the EQI values for 2013 used in the analysis for the various regions of Europe. Darker areas have greater QoG. There is a clear north–south gradient, but variability seems high also within some countries, for example Italy or France.

As for the indicator of subjective poverty, it is taken from the EU-Silc survey, and it refers to the share of persons that in each macro-region respond “with difficulty” or “with great difficulty” to the question “Is your household able to make ends meet…?”

Overall, the coefficient of correlation between EQI and subjective poverty is 0.31. Moreover, the correlation between EQI and a measure of monetary poverty (equivalent income) is 0.25, while that between subjective and monetary poverty is 0.28. Basically, the authors check whether the correlation between EQI and subjective poverty remains significant after controlling not only for different income levels but also for many other possible covariates which might be relevant in shaping the correlation at stake, over the whole sample and in different subsamples.

In other terms, the authors study the impact of QoG also considering the interrelationship between monetary and subjective poverty: if the hypothesis that government efficiency matters for living standards is correct, then the probability that a monetarily poor household does not feel itself to be poor should be higher in areas with high-quality government. Conversely, among households which are not poor in terms of relative income, there should be a greater share of subjectively poor respondents in areas with low-quality public services.

The study highlights that living in an area with high quality of government reduces the probability of feeling subjectively poor. Further, those who are monetary poor feel to be less poor when living in a region with high QoG, and vice-versa for the non-poor.

If households that live in an area with good governance feel better off than their income

would suggest, the next question is to try to evaluate the ‘premium’ of efficient government, that is what is the difference in cash income needed to reach a given level of well-being for people living in areas with different degrees of government efficiency.

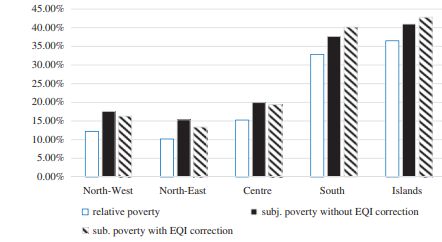

The authors propose therefore a method to obtain a subjective poverty line corrected for the level of government quality: the higher the latter, the lower the poverty line, since it is easier to have a good standard of living if the government is efficient. They obtain that good governance translates into a nearly 6% reduction in the income necessary to make ends meet, ceteris paribus. This means that the “cost” of low QoG, i.e. the major cost that households living in areas with low QoG must sustain if they want to make ends meet, is for example 1800 euro per year for a family with disposable income of 30k euro, a non-negligible amount. Focusing on Italy, it is possible to compute the subjective poverty lines corrected for the level of QoG for different macro-regions, since they are characterized by significant geographical differences in the QoG at subnational level. The result is a widening gap in the incidence of poverty between North and South, as emerges from Figure 2.

The results confirm that the effect of living in an environment characterized by good governance impinges significantly on subjective poverty, and that the quality of institutions and governance seems to matter more than their quantity.

Since poor areas within countries often go hand-in-hand with local institutions of bad quality, considering governance efficiency when calculating poverty lines produces a widening effect in the differences in poverty and living standards between different parts of a country. Official standard measures of per-capita income and poverty therefore tend to understate the differences in poverty levels across regions and countries.

To conclude, improving the efficiency of public institutions has an impact also on people’s subjective well-being, with implications for disposable income as well. These findings underline the importance of improving the quality of public services and the need to reduce the regional divide, especially in countries where these are wider.