Political alignment, centralisation, and the sense of government unpreparedness during the COVID-19 pandemic

Ferraresi M., Gucciardi G., 2021 – European Journal of Political Economy

Municipalities are at the heart of the Italian decentralised system of government. As in most other countries, they are responsible for important public programmes in the fields of welfare services, territorial development, local transport, infant schools, sports and cultural facilities, local police services, as well as infrastructure spending. These activities are easily recognised by citizens, who since 1993 have also been able to directly vote for the mayor and municipal council members. It then follows that citizens often assign a decisive policy role to the mayor as she represents the first point of reference for pursuing their interests or addressing their issues, thus enhancing citizens’ capacity to attribute policy responsibilities to the right level of government.

Nonetheless, on January 31st, 2020, the Italian central government proclaimed a national state of emergency, which entitled it to take any relevant measure to solve the crisis brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, leveraging its increased centralised authority in order to control the reproduction rate of the new coronavirus, the government progressively announced several measures that closed schools and universities, public spaces, non-essential businesses and economic activities, along with restricting the movements of individuals (colloquially referred to as ‘lockdown’). All of these measures came into force identically over the whole territory.

In a recent paper, Political alignment, centralisation, and the sense of government unpreparedness during the COVID-19 pandemic, published in the European Journal of Political Economy, Massimiliano Ferraresi and Gianluca Gucciardi ask how voters evaluate local politicians in response to a sharp change in the policy-making decision system that promotes a common policy response. To provide a convincing answer, they exploit the change in the decision-making system induced by the pandemic to study voter attributions of policy-making influence. Specifically, they rely on a panel of 103 large Italian cities (all provincial capitals) observed in three waves (2015, 2017, and 2020) to examine whether and to what extent the exogenous shift in the policy-making system affected citizens’ perceptions of local politicians. To identify this effect, the authors take advantage of the political alignment of the city council with regard to the central government and implement a difference-in-differences research design.

The hypothesis is that politically aligned cities are more influenced by the change in the decision-making process, for two alternative reasons. On the one hand, voters in these cities might find it difficult to separate and clearly identify the attribution of activities and responsibilities between the central and local governments, provided the two tiers of government belong to the same ruling party, whereas it might be easier to separate such responsibilities for voters in non-aligned cities (‘blind-spot’ hypothesis). On the other hand, citizens might perfectly identify policy responsibilities across levels of government and, hence, any effect detected at the local level simply reflects a positive or negative perception of the policies adopted by the central government during the pandemic (‘punishment or reward’ hypothesis).

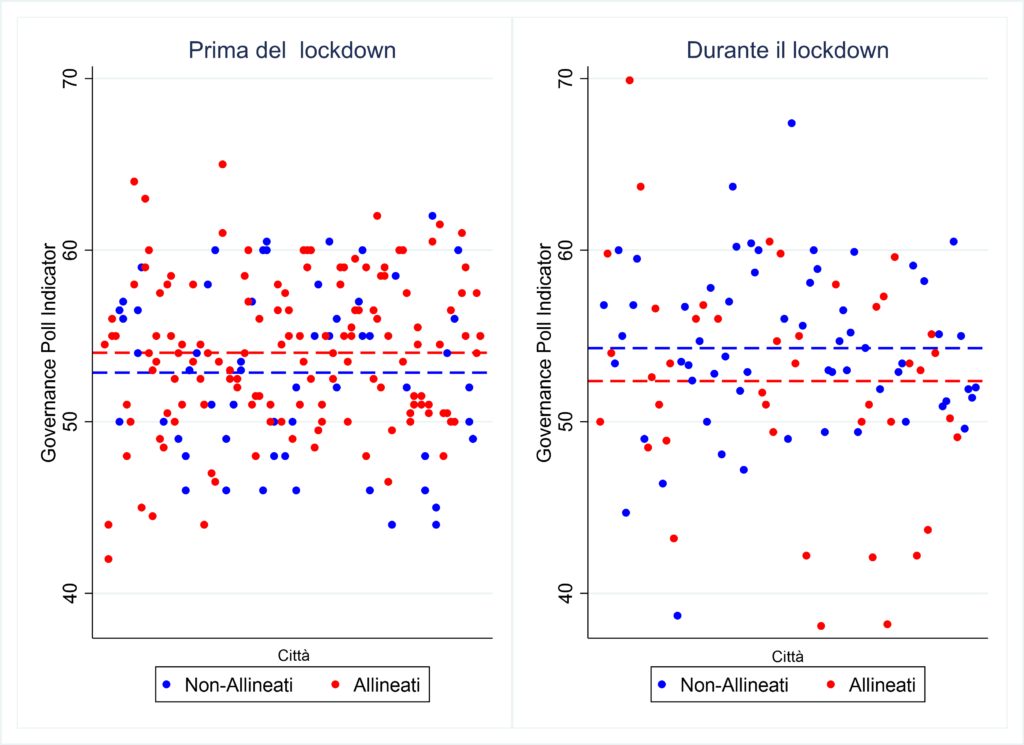

To proxy the policy-making influence that each voter expects each mayor/municipal council to exert, the study adopts the ‘Governance Poll’ indicator, a periodic public opinion poll on the approval ratings of mayors (and municipal councils). This indicator represents a local measure of ‘political’ performance as citizens do not evaluate mayors—and councils— based on their perceptions of local conditions but, rather, according to actual local performance indicators. Therefore, the authors compare the difference in the Governance Poll score between aligned and non-aligned cities before the pandemic, when policy outcomes were unambiguously attributed to the local policy maker, with the same difference during the COVID-19 outbreak, when decisions were fully centralised.

Some important results emerge.

First, when decisions are in the hands of the local governments, the attribution of responsibility is not affected by their alignment status, thus revealing that citizens are perfectly able to punish or reward politicians at different levels of government for their actions. Conversely, the governance score achieved by an aligned city during the lockdown, when decisions were fully centralised, is 7% lower compared to what it would have been in the absence of the lockdown, i.e. when policy decisions are in the local government’s own hands. Figure 1 shows this main result.

Figure 1: Difference-in-Differences estimates of the effect of lockdown on the Governance Poll indicator

Further analyses suggest that these findings are more marked (i) during pre-electoral years as compared to other years in a term and (ii) in cities with a lower level of social capital. The effect does not seem to be more pronounced, instead, in cities guided by mayors supported by large majorities. Yet, suggestive evidence highlights that the shrink in the Governance Poll indicator is associated with cities politically aligned only with the central government and not with those aligned with the regional government.

Finally, the decline in the Governance Poll indicator is entirely driven by cities located in areas less affected by the pandemic. This evidence supports the hypothesis that voter perceptions of local government performance in aligned municipalities worsen not because citizens have ‘blind spots’ that cause them to misattribute policy responsibility; rather, such a worsening seems to be driven by a sort of ‘punishment’ directed towards the central government. This last finding might be interpreted as the perception by people in these areas, which were less plagued by the virus, of a lack of government preparedness against the pandemic. Since during crises citizens always overwhelm governing institutions to some degree, they may have had different expectations for the government’s management and tackling of the pandemic. It is very likely, indeed, that citizens might have had different expectations regarding the policy responses of the government to the pandemic, and the decline in the Governance Poll indicator in cities politically aligned with the government reveals that such expectations, at least for a portion of voters, were not met. In other terms, if policies adopted by the central government are perceived as unpopular—as was the case in those areas less affected by the spread of the virus—or if there is an impression of a lack of government preparedness against the pandemic, then such a (negative) perception is exacerbated in cities whose mayor has the same political affiliation as the central government.