Corruption and tax revenues: evidence from Italian regions

Capasso S., Cicatiello L., De Simone E., Santoro L., 2022 – Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics

The relationship between corruption and tax revenues has long been the focus of attention of economists and policy makers for its negative effects on the economic system as well as on tax revenues. Since the quality of governance is crucial in conditioning the outcomes of this relationship, several recent studies present case studies related to developing countries to identify the main critical issues that affect the capacity to collect taxes.

In the article “Corruption and tax revenues: evidence from Italian regions”, recently published in the Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, Salvatore Capasso, Lorenzo Cicatiello, Elina De Simone, and Lodovico Santoro empirically examine the effects of corruption on tax revenues using data from Italian regions for the period 2003-2015.

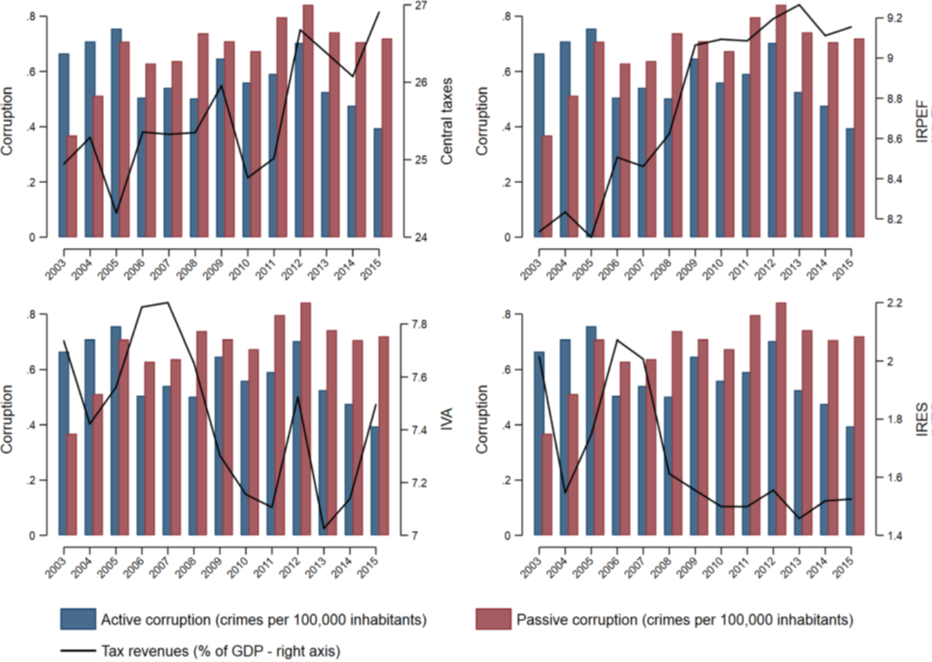

Existing literature has produced mixed results, suggesting that the impact of corruption on tax revenues can vary significantly depending on the type of tax and the specific context under scrutiny. The novelty of this study consists in introducing an important differentiation between active (coercive) and passive (collusive) corruption, corresponding to the Italian penal code offenses of “concussione” (extortion) and “corruzione” (bribery), respectively. Active corruption occurs when a public official pressures a citizen or a business, imposing a bribe payment to avoid disadvantages or administrative sanctions. This behavior often exacerbates bureaucratic burdens and undermines public trust. Passive corruption, conversely, arises through a consensual agreement between a public official and a citizen or business, who voluntarily pays a bribe to receive preferential treatment or favors, typically in the form of bureaucratic simplifications or reductions in administrative obligations. As shown in Figure 1, corruption crimes appear significant over the period analyzed. In the early years of the sample, active corruption was more prevalent than passive corruption; however, this trend reversed from 2006 onward.

The authors argue that active corruption has a more significant negative impact on tax revenues compared to passive corruption, as it more deeply undermines citizens’ perceptions of fairness and trust in institutions, thus incentivizing tax evasion and reducing voluntary compliance. Conversely, passive corruption is believed to have more limited effects on taxpayer behavior, as it typically involves individuals already inclined toward tax evasion or avoidance.

To empirically test this hypothesis, the study employs detailed regional data on tax revenues from personal income tax (IRPEF), value-added tax (IVA), and corporate income tax (IRES), alongside annual data on corruption crimes collected by ISTAT, clearly distinguishing between extortion and bribery. The econometric analysis uses robust methodologies, such as the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), to address potential endogeneity issues arising from the bidirectional relationship between corruption and tax revenue.

The analysis confirms that only active corruption has a significantly negative effect on overall tax revenues, with a particularly strong impact on corporate income tax (IRES). Passive corruption, on the other hand, does not show statistically significant effects on tax collection, indicating that the nature of the relationship between administration and citizens deeply influences tax collection capacity.

One possible explanation for the negative relationship found between active corruption and direct taxes like IRPEF and IRES suggests that corruption facilitates informality and thereby encourages tax evasion: firms may opt for the informal economy to avoid interactions with perceived corrupt officials, making the relationship between corruption and corporate tax negative. A second potential explanation refers to the literature on tax saliency which indicates that taxpayers perceive the tax burden more significantly when taxes are paid periodically in larger, more visible amount, as it occurs with IRPEF and IRES, compared to indirect taxes such as VAT, paid frequently in smaller, less visible amount. Consequently, taxpayers might respond to a high incidence of corruption by adopting stronger evasion behavior precisely in the case of more salient taxes.

The study acknowledges some methodological limitations, especially the inability to adjust tax revenue data for the propensity to evade taxes, as detailed regional data on the tax gap for each type of tax are not provided. The authors hope that future research will fill this gap if such data become publicly available. Nevertheless, the results offer significant insights, highlighting that specific forms of corruption, particularly active corruption, are more harmful than others in affecting negatively tax revenues. Therefore, implementing effective internal controls to curb coercive corruption, enhancing fiscal transparency, and strengthening administrative integrity and accountability are essential issues in reducing discretion and opacity that facilitate bribery. Finally, fighting corruption should be a priority in public policy, especially considering that political connections of citizens and firms are often a major source of tax evasion in highly corrupt environments.